It started with a tin lunch bucket, donuts cooked in bacon grease, and bib overalls with snap buttons. Likely as not, that’s what Almon “Al” Manchester had with him when he and his team of horses dragged a sled piled high with his masonry supplies. The trowels, the hammers, the sand, and the tin buckets of water were dragged across the snowy fields and frozen ice, rather than following the longer, road route. It was the winter of 1911 and Almon was stockpiling stones that he had pulled from nearby stone walls so that he could build a rare architectural gem, now known as one of Maine’s most elegant barn venues for weddings and events: the Stone Barn at Sebago Lake in Standish.

In building the Stone Barn, Almon Manchester helped to fulfill a dream of Harry Verrill or “Lawyer Verrill” as Manchester called him. Harry and Louise Verrill commissioned Manchester for a number of stone masonry projects on both sides of the Whites Bridge Road. The largest of these was to build a Normandy-style stone barn located on what is now the Saint Joseph’s College of Maine campus–a building that remains unique in New England.

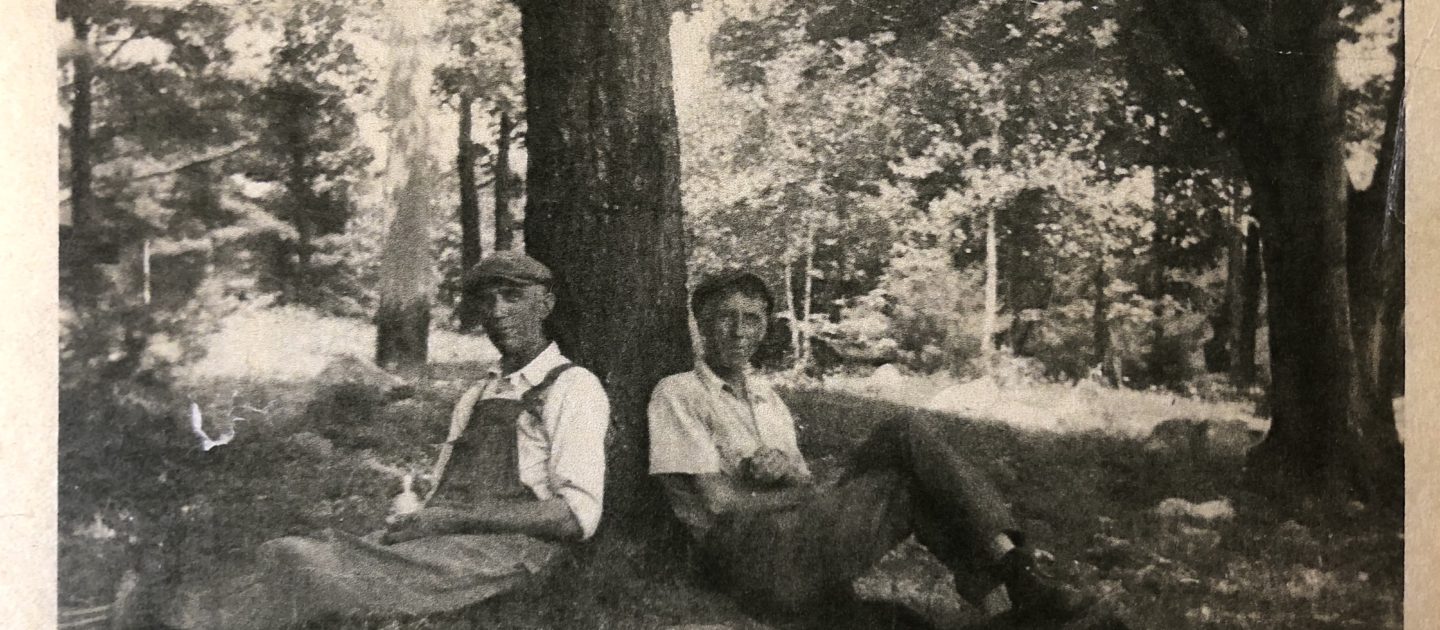

Stone Barn mason Almon Manchester (left) and his brother, Warren Courtesy: Don Rich

“It’s good to grow up and have our ancestors tell us what they can.”

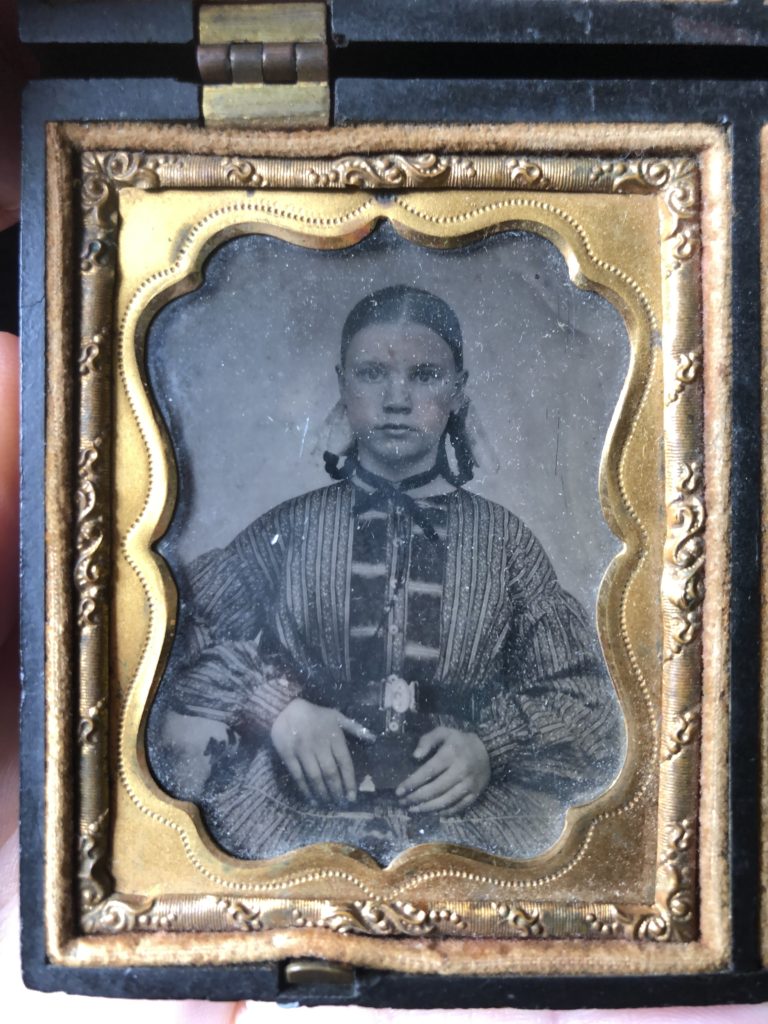

Verrill’s plan to establish a farm–albeit a gentleman’s farm– had considerable precedent on his estate in Standish. The property, stretching up from the lakeshore and encompassing hundreds of acres, had been worked by generations of farmers. Headstones were already poking up in a cemetery plot across from the site of the barn’s construction; their carvings dated back to the early 1800s and bore names of other early settler families, such as the Shaws. Verrill would have known that the agricultural history went even further back, beginning with the Wabanaki tribes who planted corn, beans, and squash in villages along the river and around the lake.

Verrill would have known this history because his mason’s ancestor, Stephen Manchester, was one of the legendary settlers of New Marblehead who fired the musket shot in 1756 that killed Chief Polis (also known as Polan or Poland of the Sokokis). Almon Manchester’s family roots extended back many generations into the 1700s, to an era when Windham was known as New Marblehead, Standish as Pearsontown, and the region still belonged to the Province of Massachusetts Bay. Almon’s ancestor, Stephen, also built the family homestead, a farmhouse that-despite being moved twice–still houses Manchesters and welcomes their extended family back for annual Memorial Day reunions.

Stephen Manchester was heralded, by fellow settlers and their descendants, as a hero who helped defend against tribal attacks and brought to an end the conflict between settlers and tribal peoples. Wabanaki peoples, on the other hand, experienced the conflict as a fight for their traditional rights to live on the land and fish–salmon, bass, and trout–from the sea to Sebago Lake along the Presumpscot River. Not only were settlers taking over traditional tribal lands and converting it to farmland, but they also were damming the river, effectively killing the fish runs. So disruptive were the dams that Polin and his tribe appealed to the governor in Boston on more than one occasion. The governor apparently agreed with Polin and decreed that the dams needed to include a fish passage. That compromise never occurred before Polin’s death.

Stone walls around Stone Barn at Sebago Lake Photo: Patricia Erikson

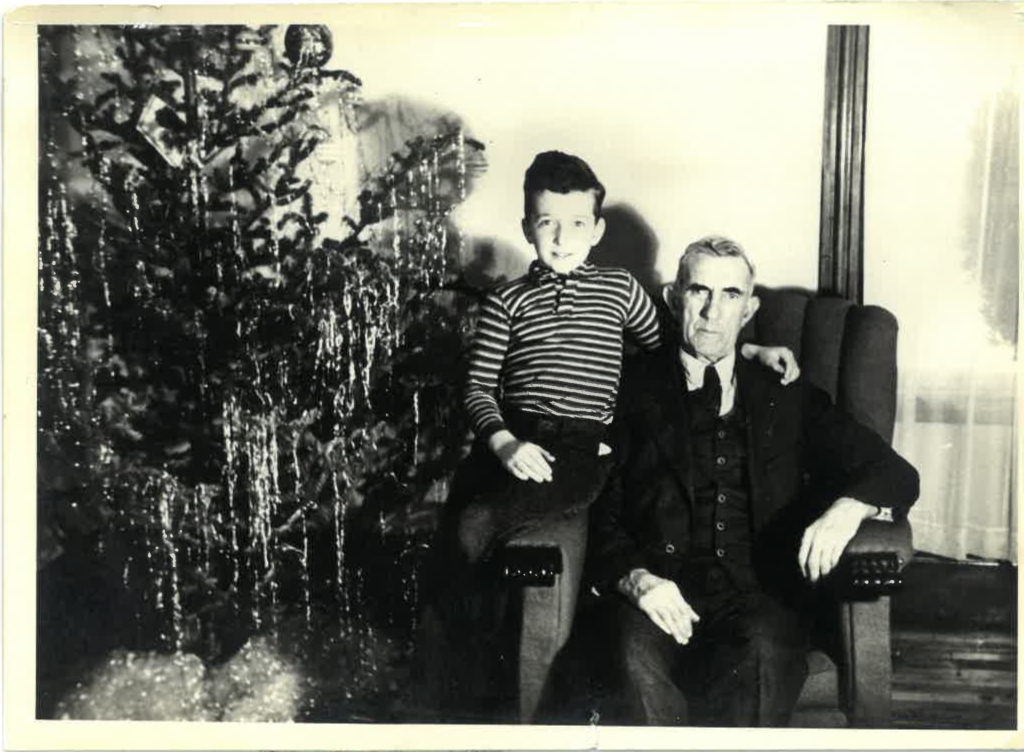

But by the time Almon Manchester was building the Stone Barn at the turn of the 20th century, these stories had been relegated to history books, poetry, and family lore. Almon Manchester’s grandson, Don Rich of Windham (born 1934), still remembers his grandfather’s stories about how he worked with the stones and how he built the Stone Barn, “He gathered the fieldstones from the stone walls around Standish. The tenders–the mason’s assistants– would have dragged the stones out of the woods, mostly by horses and drags, and brought them to the building site. It took a couple of tenders to support the mason. They would bring thirty or so stones over so that Almon could visualize his artwork. He was a traditional craftsman. He would make sure that each stone fit together. ‘Every stone had to have a face,’ he would say. And the corners had to have two faces.”

“I remember he told me how they worked in the winter under tough, off-season conditions. They put barrels up on stones and build a wood fire underneath. Granddad boiled water to make the cement. They packed sand around the fire to warm the material up. Then they mixed two or three shovels of sand to one shovel of cement in the mortar pen. They hoed and mixed it and then added warm water. The tender would put the fresh mortar or mud on the mason’s trowel. That trowel was like his palette. If the ‘mud’ didn’t please him, it needed to be fixed. He used a jointer to press and draw the mortar between the joints. The mortar remained recessed in this traditional way so that the stone face would be the prominent feature.”

“Granddad smoked cigarettes. He would sit in a relaxed position. He had this slow, deliberate way of talking. He used to tell me stories as I worked alongside him on his jobs, stories about what he did as a young man. It’s good to grow up and have our ancestors tell us what they can.”

The former estate of “Lawyer Verrill,” now the campus of Saint Joseph’s College of Maine, still organizes gatherings–from farm-to-table dinners to sustainability festivals– that draw together everyone from the descendants of the Manchester settlers to Wabanaki tribal drummers.

Not only do the granite stones of the Stone Barn endure, so, too, does the agricultural tradition and the love of telling stories.